Lost Roman town of Sitomagus

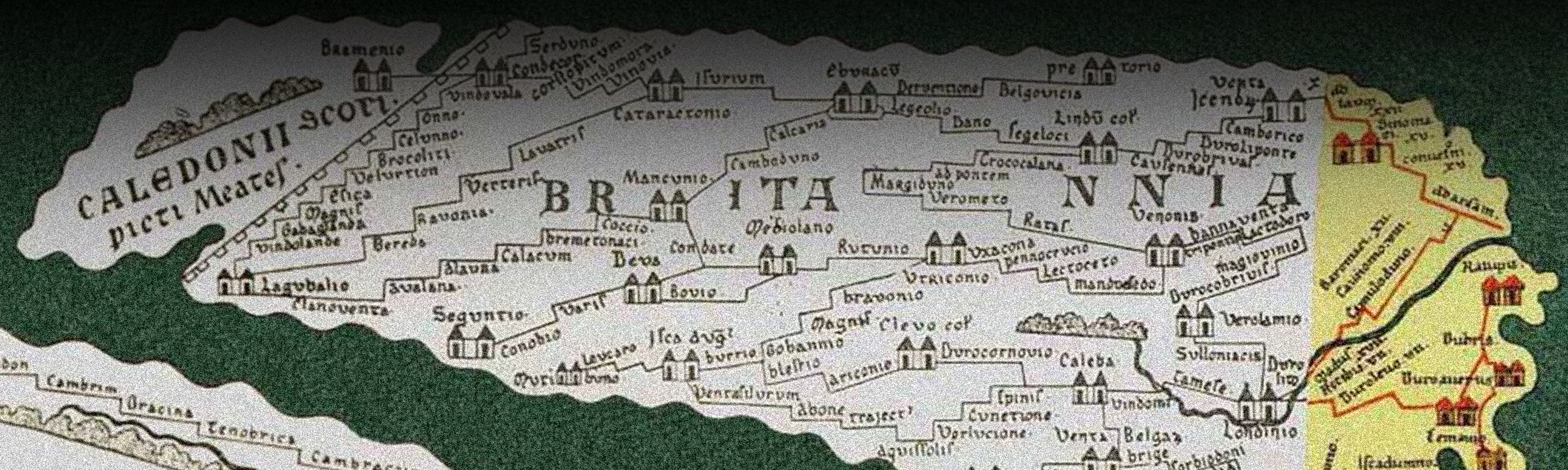

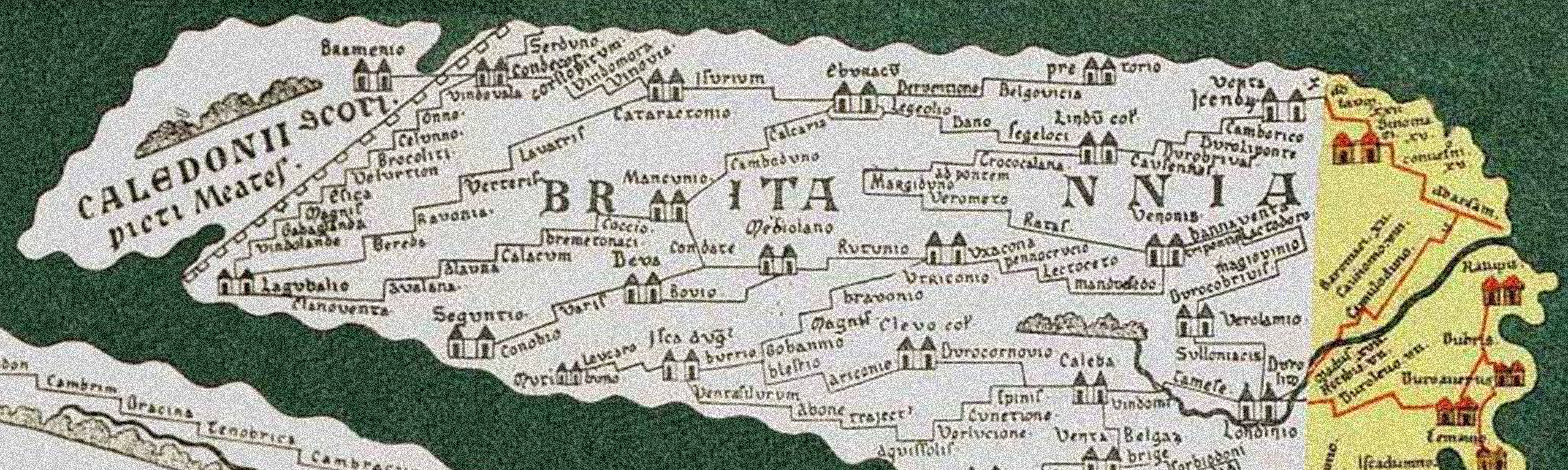

The Roman town of Sitomagus is the first station recorded in the Antonine Itinerary, a 3rd century register of stations and official routes via Roman roads. Itinerary IX gives the position of Sitomagus, although its location today is largely considered ‘lost’.

Physical evidence for the presence of Roman occupation is scarce and relies on surface finds evidenced in field walking where pottery scatters and building materials may sit beside isolated artefacts. Intense farming practices and coastal erosion mean that much of the interpretation regarding Roman occupation and activity involves “engaging in analysis of an essentially hypothetical nature”.[1]

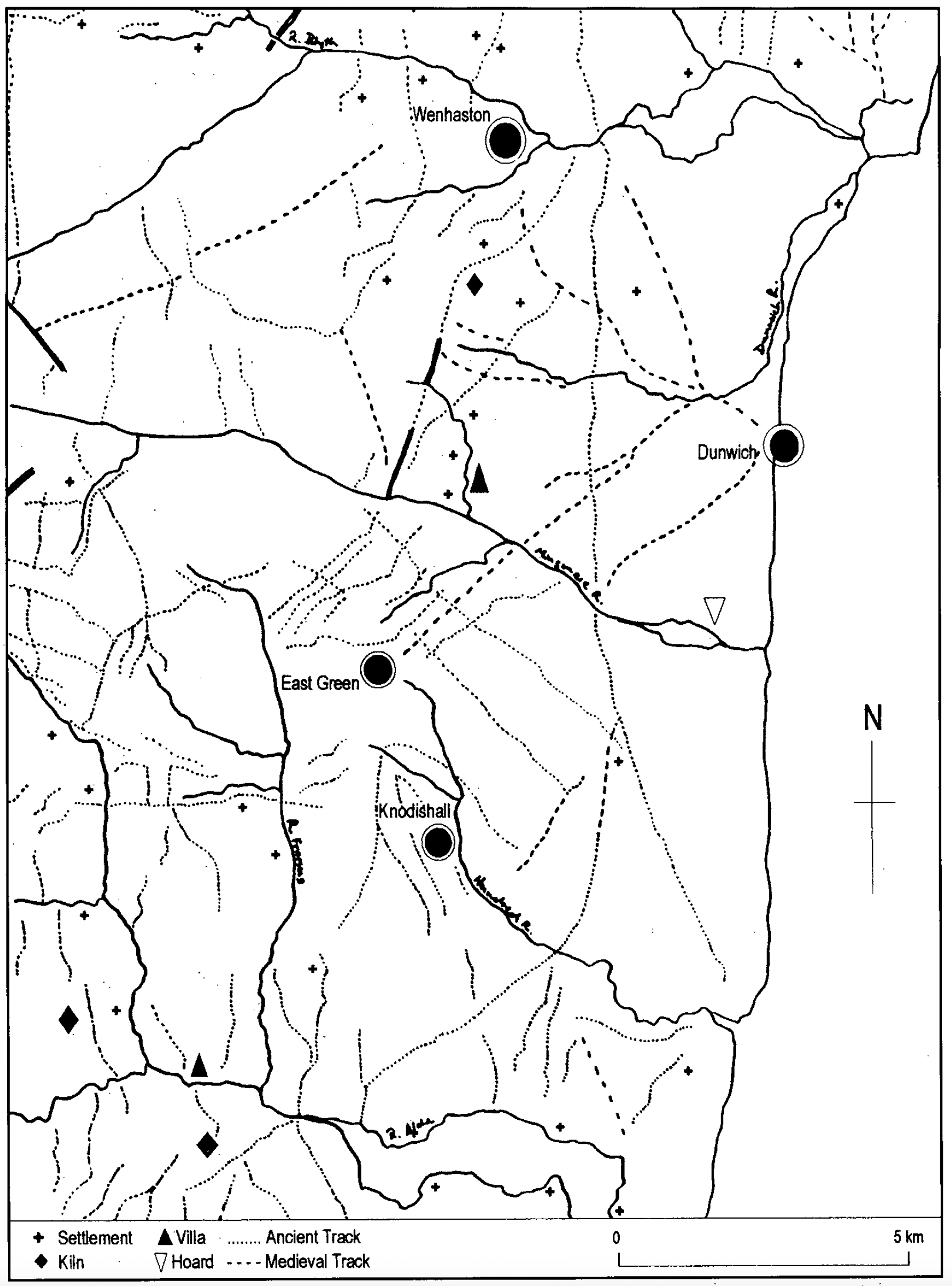

The general lack of building stone readily available in Suffolk meant that few Roman roads had a paved surface, with most recorded roads showing the remains of gravel, such as the Peddars Way that runs from the Suffolk border to the north-west border coast. At 45-50 miles in length in its north-west section, it stretched across East Anglia before reaching the North Norfolk coast and travelled eastwards totalling 93 miles in length and was as much as 2.5 feet deep and up to 13 metres wide. Any stone that was available to be used for buildings would most certainly be reused and dispersed more widely. Roman tiles were reused in the Greyfriars monastery at Dunwich, the ruined Chapel at Eastbridge (Leiston Old Abbey site) and bordering Knodishall at Leiston in the current Abbey site that was built later than its predecessor in 1362 AD, all of which suggests that Roman occupation of the sites is likely to have existed.[2] Just over four miles away from Knodishall at Blaxhall, a Roman bath-house was discovered and excavated in 1971 beside large quantities of metal working slag and Roman tiles.

As the register was supposed to aid route planning, topographical accuracy was ‘not an important consideration’.[3] A 13th century copy of an original Roman map showed a ‘Senomagus’ on the East coast in relation to the main imperial road system, however at the time the copy was made many of the British sections were missing. Another earlier Roman manuscript of early 3rd century date describing 225 imperial roads lists Sitomagus as being situated 29.5 miles from Caistor St Edmunds, south of Norwich and 22 miles from Combretovium (Coddenham, north-west of Ipswich).

Over the years, various Suffolk locations have been proposed for the site of this lost Roman town, including Peasenhall, Yoxford, Saxmundham, Thetford, Ixworth, East Green, Dunwich, Wenhaston and the much-preferred Knodishall that borders Leiston. The distance from Knodishall to a variety of locations, including from Caistor via Margary’s route 36 at 31 miles is favoured by Robert Steerwood in 2003 for the Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History.[4]

Knodishall appears to be the site of at least one Roman villa or substantial farm complex, evidenced from the roof and flue tile tesserae where the site may have operated as a local administrative centre with some occasional trading or market function. A bronze head stud brooch, estimated to be of 2nd century date was also discovered close to the site in 1973. The case for Knodishall seems positive, supported further when in 1972 a surface scatter of Roman material was reported.[5]

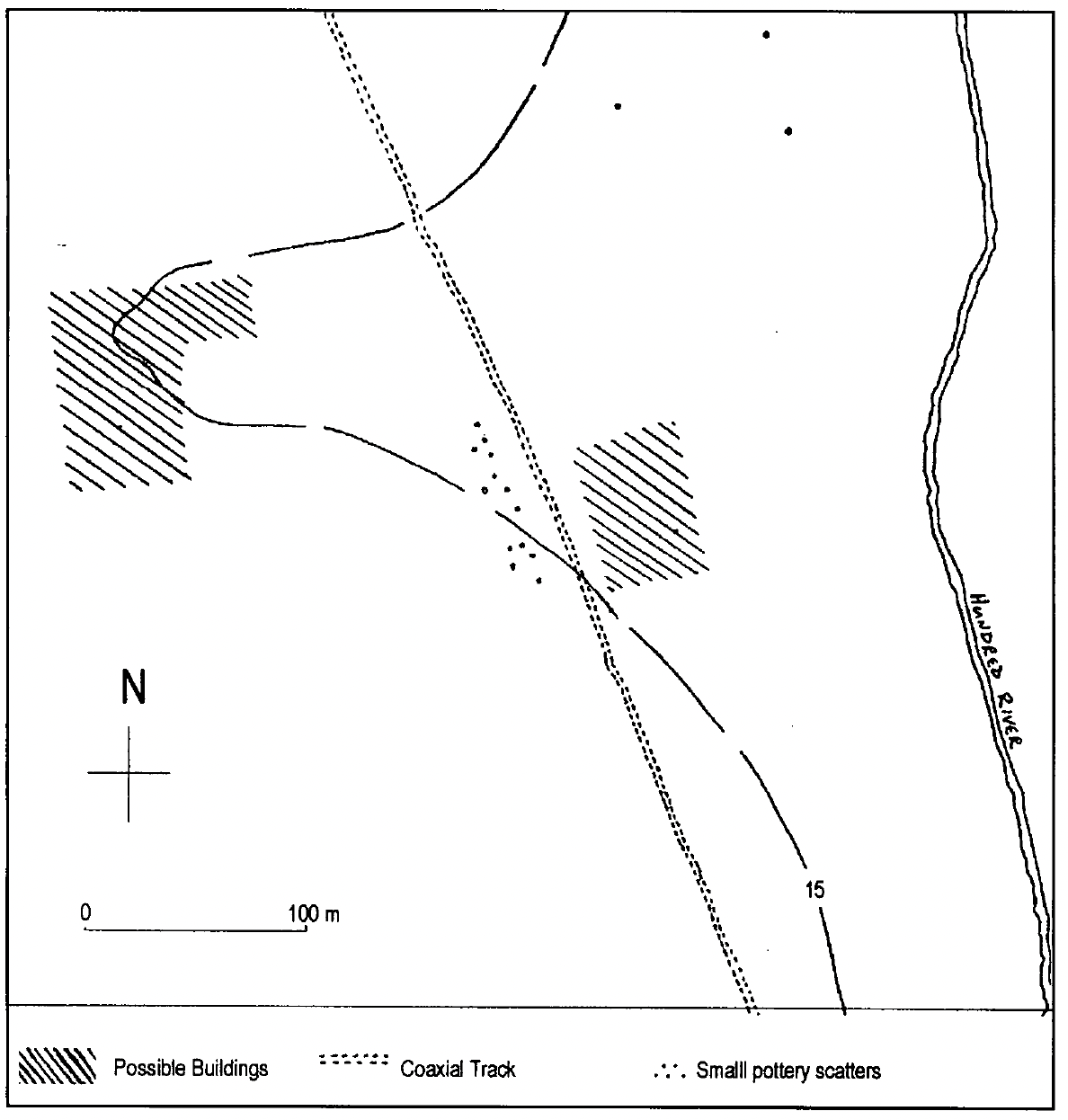

However, nearby East Green appears to be a more favourable fit if one considers the question of what lay at the precise location indicated by the distances described in the Antonine Itinerary. The early medieval topography of East Green, particularly its long wide field, has also been considered to be of worthy note.[6] Medieval field boundaries in the Eastern and Central zones of England were known to use the same Roman boundaries up to as much as 70% of the time.[7] Such continuity, where human actions have been informed by the remains of past societies and communities has been called the longue duree.[8] Containing a network of intense coaxial trackways that all connect to East Green, it is possible that additional crop marks detectable at several locations[9] cause East Green to merit serious consideration.

References

- Steerwood, R. (2003) A context for Sitomagus: Romano-British Settlement in the Suffolk Mid-Coastal area; Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, vol. XL Part 3 pp. 253-261

- Sear, D., Murdock, A., LeBas, T., Baggaley, P. & Gubbins, G. (2013) Report 5883 Dunwich, Suffolk: Mapping and assessing the inundated medieval town. Unpublished report.www.dunwich.org.uk/resources/documents/dunwich_12_report.pdf

- Steerwood, R. (ibid)

- Steerwood, R. (ibid)

- Steerwood, R. (ibid)

- Steerwood, R. (ibid)

- Rippon, S. (2018) Kingdom, Civitas, and County. The Evolution of Territorial Identity in the English Landscape. Oxford University Press.

- Semple, S. (2010) In: the Open Air. in Carver, M., Sanmark A., & Semple S (eds). Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited. Oxbow Books.

- ‘Millennium Map’ aerial photographic survey (2000), NGR ref. TM 403656 www.getmapping.com