Campsea Ashe Ritual Animal Burials

Eight animals buried East-West 1st – 2nd century A.D.

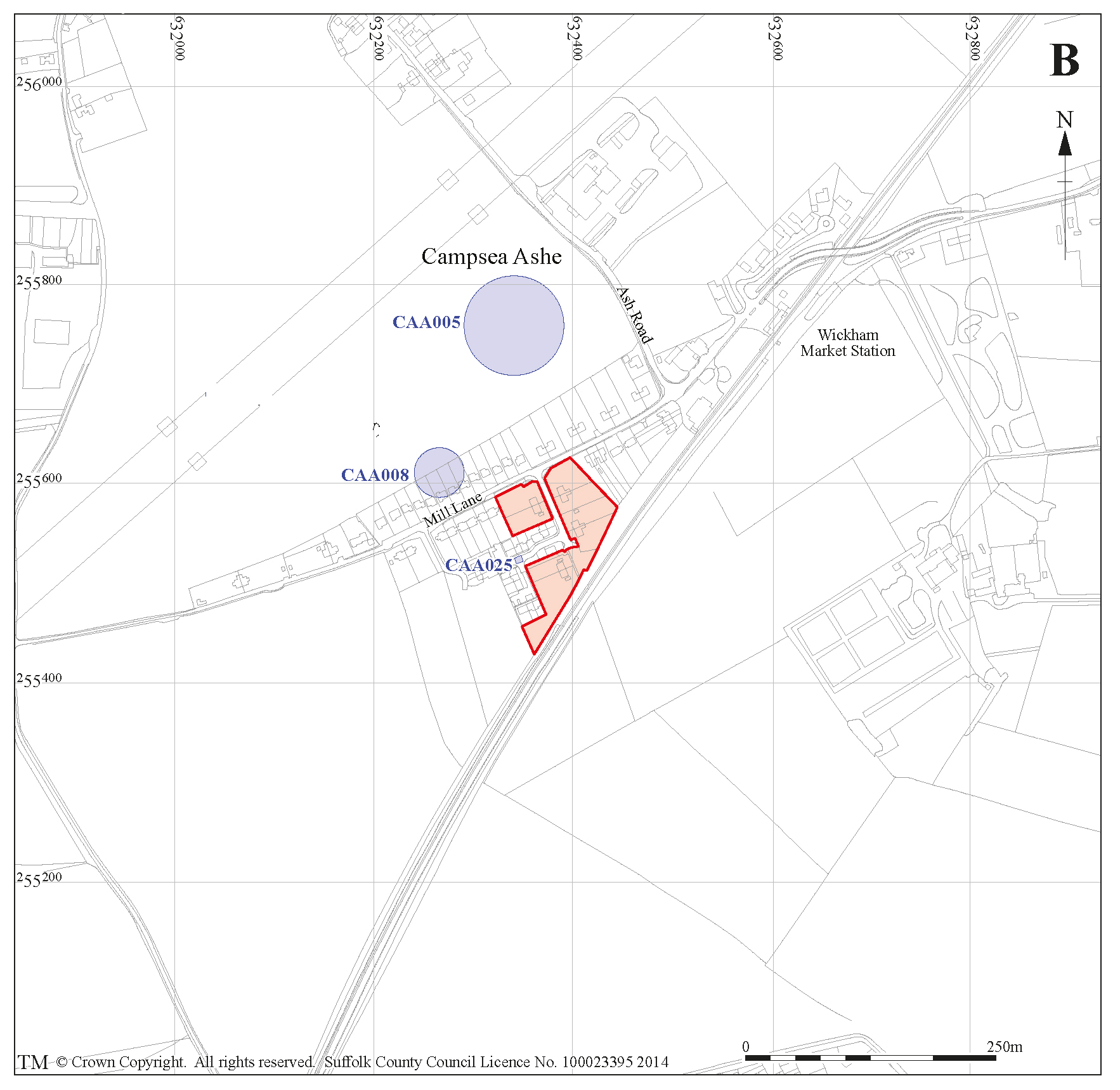

As part of a housing development in 2013 at Ullswater Road, Campsea Ashe, preliminary excavations yielded an urned cremation burial of probable Bronze Age date, along with ditches and gullies dating to the Roman period. Due to these positive results further excavations led to the rare discovery just off Mill Lane and to the East of a woodland, The Oaks, of eight complete or near complete animal burials. These are rare because out of the 1,500 square miles in the county of Suffolk, only two other Roman-British animal ritual deposits have been discovered at Mildenhall and Hacheston. That said, the animal burials at Milldenhall turned out to be two modern day 20th C animals, buried as a result of farming practices ‘randomly’ on top of two earlier Iron Age sheep skeletons [1].

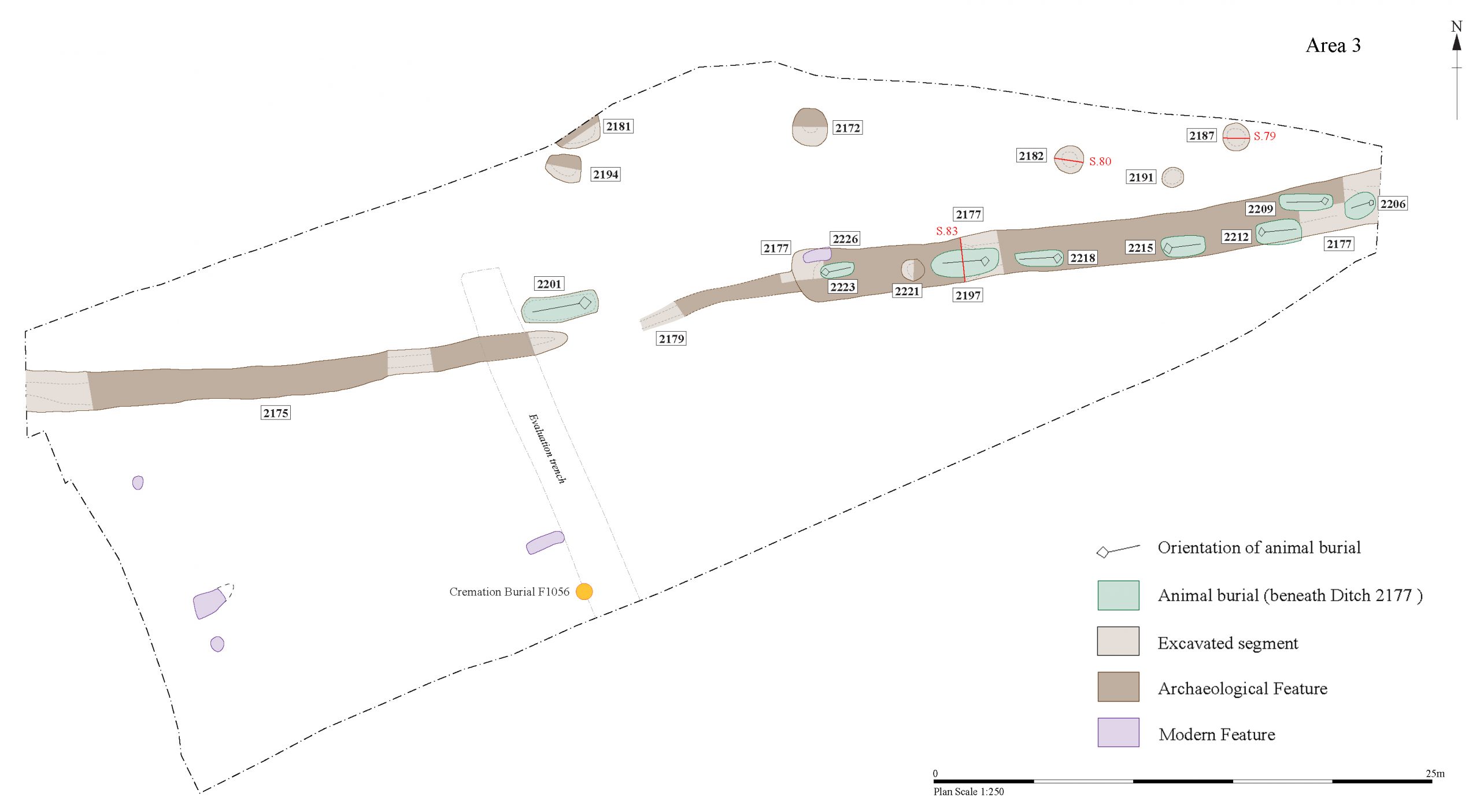

Consisting of a horse, boar, and six cows, the animals were recovered from a line of individual pits amongst a series of Roman dated boundary ditches and features from the 1st – 2nd century A.D. It is curious that one of the burials included part of a foetal or neonate horse, with each animal painstakingly buried in its own interred separate pit. Six of the burials were located on a near perfect East-West alignment and lay in a straight East to West row. Whilst the head of the foal burial was missing, numerous skull fragments and a mandible were recovered from the base of the ditch within the area of the burial pit which probably originated from this animal. A further eleven bones of a foetal or early neonatal foal were also recovered.

Given the early date for these burials and the Pagan beliefs current at the time, these burials are believed to be sacrificial, serving no functional purpose as to why the animals were buried in the manner that they were. The deposition of animals as placed deposits in the slightly later Christianisation period were for a variety of reasons and to achieve various ends. These could include renewing the settlement boundaries or exercising control over the entrances and doorways, thus negotiating the ‘liminal times’ around the creation, construction, and destruction of buildings [2]. Today, the meaning behind these highly ritualised and symbolic deposits we can only but wonder.

The use of alignment can link an individual with their surrounding landscape, and as such, cannot be separated from artefacts and have been used to substantiate a vital component of the human condition since at least prehistoric times, often in relation to death and burial. The usual orientation for inhumation in late antique early medieval cemeteries was East-West. East-West axial alignment is also considered to be one of the features of late antique early medieval settlements that could also include non-architectural features such as wells and crosses [3].

As well as the animal burials, there were pieces from two querns and one being a puddingstone. ‘Puddingstones’ are natural boulders of conglomerate material believed to be formed by the grinding action of Ice Age Glaciers. These puddingstones (they look like a traditional spotted dick pudding) attracted a great deal of symbolic attention from our ancestors, becoming known as ‘mother stones’ and were venerated as sacred to the mother goddess. The term ‘foundation stone’ relates to the practice of building later ecclesiastic buildings, such as churches, on top of another stone of equal importance, commonly the ancient Pagan stone of the time, and the foundation stone was the symbol of that ancient mark stone which originally ‘founded’ the site. Were the animal deposits and the puddingstone somehow related in symbolic terms?

References

1. Morris, J. (2012) The Ritual Killing and Burial of Animals: European Perspectives.

2. Sofield, C. M. (2015) Anglo‐Saxon Placed Deposits before and during. Christianization (5th–9th c.). In C. Ruhmann, & V. Brieske (Eds.), Dying Gods: Religious Beliefs in northern and eastern Europe in the time of Christianisation. Internationales Sachsensymposion; No. 2013. Niederssächsiches Landesmuseum Hannover.

3. Blair, J. (1992) Anglo-Saxon Minsters: A Topographical Review. In Blair, J and Sharpe, R (eds.). Pastoral Care Before the Parish (Leicester).

Illustrations reproduced from CAA 032.

Archaeological Post-excavation Assessment. SCCAS Report No. 2013/131.

© Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service.